“Passive income” is a relatively newly minted oxymoron. I’m not certain exactly where the term originated, but my best guess would be real estate and investing. The idea of rental income or dividends steadily filling a savings account over the course of the year is intoxicating (mostly to the Olds).

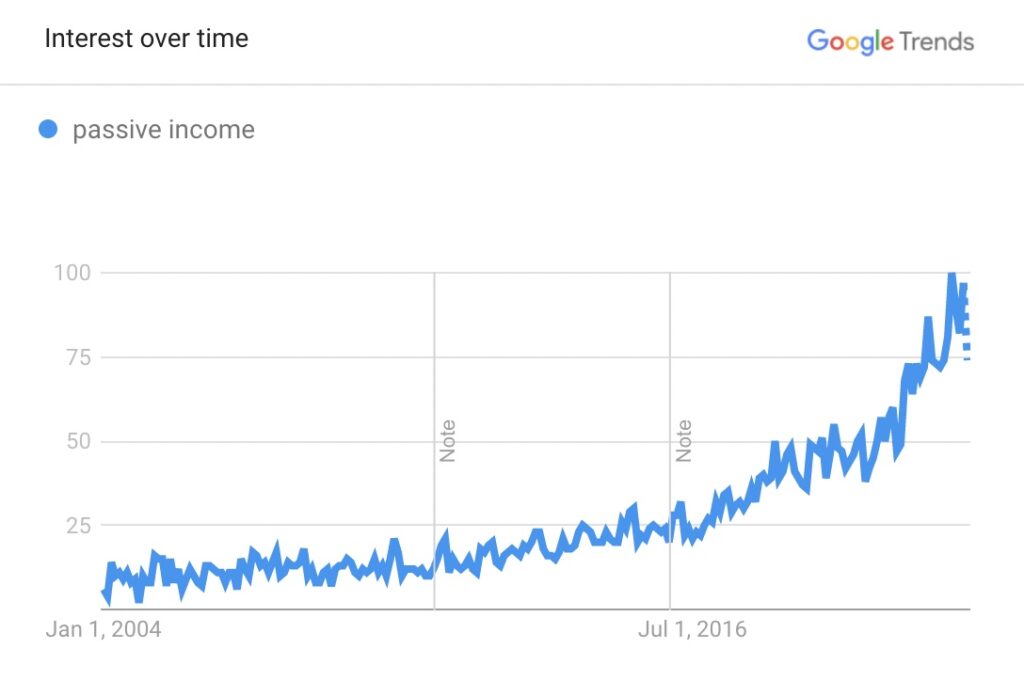

“Passive income” is trending up in Google Trends from around 2012-2013 onward. Monetizing “content” and the internet economy probably has something to do with this.

The investing podcast “Animal Spirits” recently had a conversation about how passive income is actually quite active. Plunging plugged toilets is far less exciting and less passive than sitting on the couch and checking a bank statement, as is tracking down and paying plumbers to plunge said plugged toilets for that matter.

Writing blog posts each month, each week, or three times each week as I was when I first started blogging is the equivalent of plunging cultural toilets (to loosely borrow a concept from Murakami). Generating money from online content seems like it would be a fun, “passive” thing to do, but I think that’s only in comparison to a regular 9-5 job. It’s actually a good bit of work, and there are very few who are able to turn a content library into a full time job. Even then, once your consumers are accustomed to a schedule, you have to feed them or risk them leaving for fairer content pastures. I get far fewer commenters on my blog posts now than I did when I had something for them to read every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

In September I wrote my fiftieth column for the Japan Times Bilingual page. This is kind of crazy for me to think about, mostly because I vividly remember writing my ninth column during the winter of 2014. It was a cold, snowy Chicago weekend during the extended polar vortex that year. I was single and lonely, but I hadn’t written for the paper in nearly two years, so I was happy and fulfilled at the prospect of being paid for my writing again, and of having something to say.

I put on Beck’s “Morning Phase,” which I believe was streaming as a preview on NPR before the album release, made a cup of tea, and sat in front of the computer for most of the day. It was great.

At some point I stepped outside onto the back staircase of my apartment and took a photo of my mug with the weather.

And I tweeted out a preview of the article I was working on:

A line from Cowboy Bebop I’ll never forget: のんきなやつだな。Oh, that Spike. #anime

— Daniel Morales (@howtojapanese) February 15, 2014

Being a writer these days is a bit like being the captain and sole crew of a ship. You put up new sails, take others down, redeploy things from the past, all in the hopes that a breath of wind will come along and propel you forward.

Strangely enough, this article got a draft from the official Haruki Murakami Facebook page:

There’s a difference between attention and money. The plug on this page got that article far more clicks than it otherwise would have had, and I imagine that didn’t hurt my chances to keep writing for the JT. In a sense it increased my potential earnings. But it wasn’t money in the bank.

I got a more financially lucrative gust of wind earlier this spring when Keio University used one of my articles (“Japanese humor: more universally funny than you think”) on their entrance exam.

My initial reaction:

But it wasn’t totally unexpected. Starting in 2011, I received half a dozen or so requests to reprint a few of my JT articles in Japanese textbooks for prep study courses. I was confused at first but later it became a nice surprise; I would wake up in the morning bleary eyed, find an email from the JT asking me for reprint permission and my author’s fee, and punch in a quick reply.

In these cases, I received money but no attention. The small author’s fees dropped into my bank account silently a month later.

But Keio was big enough that it set off a quick series of requests. Not a huge amount, but about the same as in the previous few years. It’s been a nice little windfall.

And now that I look back at my emails (that I clearly wasn’t reading closely enough), I’m realizing that another article (“Tanka help Japanese express emotions”) was used on the entrance exam for Fukuyama City University and that Senshu University used the same article on their test that Keio did. Crazy.

The last reprint request came in October, and I asked for a 15-dollar increase to cover the international wire fee I get charged by my bank. I haven’t heard back from the JT, so I may have accidentally shut off my stream of passive income, although it’s never been clear to me whether the JT is shopping around my articles (and their own content library, which is quite vast) or these prep courses and universities are discovering the writing on their own.

I did discover that university entrance exams have a history of “borrowing” material from foreign writers. Tim Murphey of Dokkyo University wrote an article in 2005 for “Shiken: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter” titled “Entrance exams breaking copyright law? Academically unethical?”

It sounds like things have changed for the better in the past 13 years. As you can see above, I was cited, which wasn’t always the case. However, the JT and I were only paid because the test question was reprinted in an exam book. They didn’t have to ask permission or pay us to use the writing on the original exam, which feels a bit strange.

I’m not getting my hopes up that the work I’ve produced will bring in a massive amount of passive income. This next statement might come from a place of extreme privilege (this is me checking my proverbial self before I wreck my proverbial self), but I’m not sure if earning money was ever the point. I started writing How to Japanese because I needed to produce something. I needed to connect with people and share things. There was a sense of justice, a light outrage that no one was able to communicate certain things to me. And I wanted to pass those things on.

It feels good to have succeeded on that front, to be reaching out from my laptop onto the screens of others learning Japanese. And now onto the pages in front of Japanese high school kids taking their entrance exams…who hopefully glean something from my words despite the testing fervor that surrounds them.

I do appreciate the extra income, but mostly as a trophy of sorts because I know how awful a writer I was at age 23, and I know how actively I had to work to get where I am now.

Pingback: These Are the Goods

Pingback: How to Japanese at (the Entrance to) Keio University | How to Japanese